Grandville Bête Noire annotations - page 2

This is similar in concept to the Directors Cut of Heart of Empire that Bryan and myself created: it is an attempt to answer the eternal "where do you get your ideas from?" question, and a way to showcase the influences and images that went into the creation of Grandville.

Below are the annotations for the Grandville Bête Noire pages 21 to 40.

We are publishing updates to this page every Sunday and we will cover the entire Grandville series. Also see the annotations to the first Grandville Graphic Novel, and the second, Grandville Mon Amour.

Start reading the annotations below, or jump to page 21, page 22, page 23, page 25, page 26, page 28, page 29, page 30, page 31, page 32, page 33, page 34, page 35, page 36, page 37, page 38, page 39 and page 40.

Page 21

Panel 2

Occam’s Razor is the principle that the simplest explanation, the one that contains the fewest assumptions, is usually the correct one.

Panel 4

“By Timothy!”: The favourite expletive of Francis Durbridge’s popular fictional crime fiction author and amateur sleuth Paul Temple, created as a BBC radio serial in 1938, later made into films, a TV series, novels and a comic strip in The London Evening News. The last Paul Temple radio drama was first aired in 2013. You can still listen to reruns of the adventures from time to time on Radio 4 Extra, which often repeats many detective dramas, including the Sherlock Holmes stories and Edgar Wallace’s The Mind of Mr JG Reeder:

Page 22

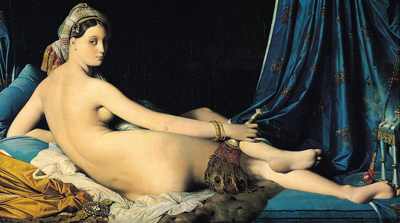

Billie’s pose in this scene is taken from La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Page 23

Panel 3

George Meles: Meles is the badger genus. “George Meles” is taken from George Melly (how meles it would be pronounced in French), the British writer and jazz singer who, among other things, scripted the newspaper strip Flook (see Mon Amour annotations page 53).

Panel 5

In the left foreground is a statuette based on Rodin’s Le Penseur (“The Thinker”).

Page 25

Panel 4

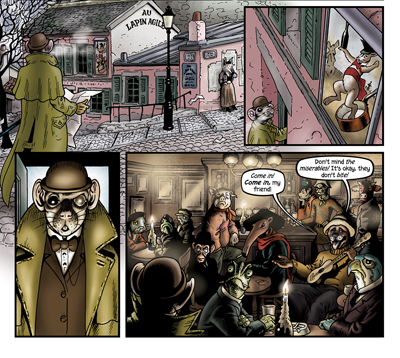

Au Lapin Agile: A famous cabaret in Paris’s Montmartre district. It’s been there since around 1860 when it was called Au Rendez-vous des Voleurs (“At the rendez-vous of thieves”), later Cabaret des Assassins.

It acquired its current name after the artist Andre Gill painted its sign in 1875, a picture of a rabbit jumping out of a saucepan, when it came to be called Le Lapin á Gill (“Gill’s rabbit”), which evolved into Le Cabaret au Lapin Agile (“The Agile Rabbit Cabaret”).

In the early 20th century, it became a favourite hangout of artists, including Picasso and Modigliani.

Panel 7

In the right background, the couple are based on Picasso’s Au Lapin Agile (1905), a painting commissioned by the proprietor Frédérick Gérard, who’s depicted in the background of the painting.

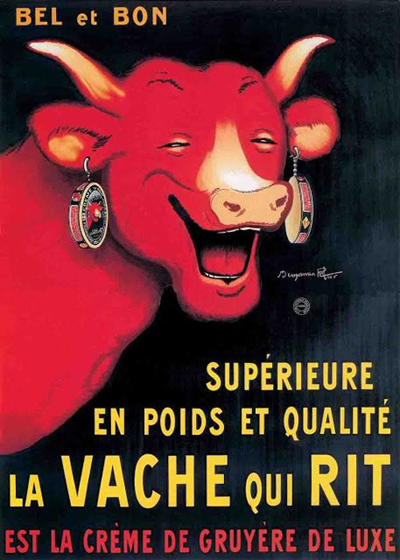

Just to the right of him is a character based on La Vache Qui Ri (“The Cow that laughs” or “The laughing Cow”), a brand of processed French cheese made since 1865. In 1924, the French illustrator and comic artist Benjamin Rabier, who produced many children’s albums of anthropomorphic characters, created the cow by which it’s known, though today it’s a slicker modern version.

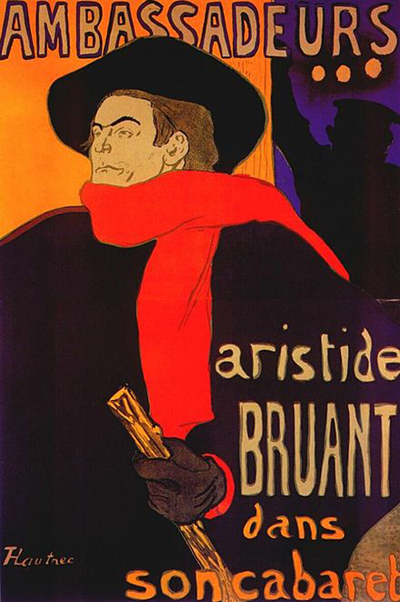

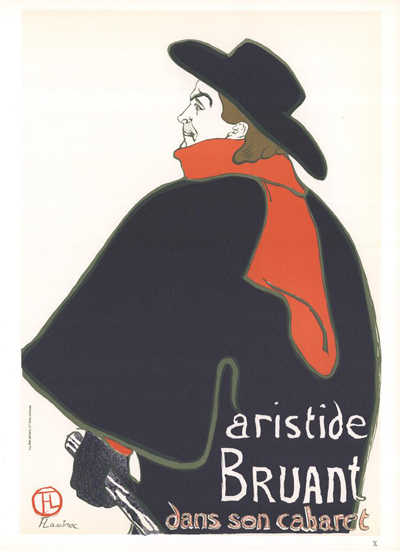

The anteater in the red scarf is a reference to Artides Bruant (1851 – 1925), cabaret owner and performer, who bought the Lapin Agile to save it from demolition in the early 20th century, seen here in a couple of posters by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Toulouse-Lautrec (1868 – 1901) is himself parodied here by the chimpanzee sitting next to him.

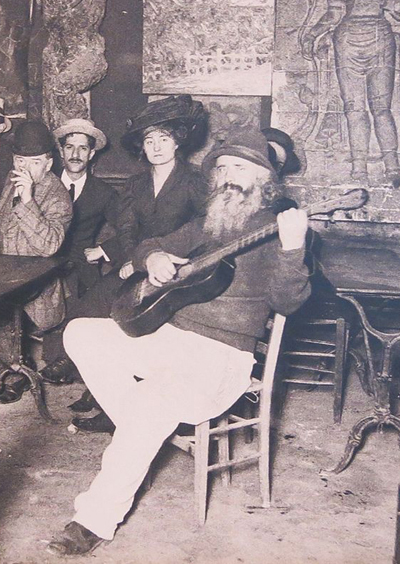

The proprietor with the guitar, wearing a hat is a nod to the aforementioned Frédérick Gérard, nicknamed Le Pere Frédé (“Father Freddy”, which he calls himself next page). Here he is in his bar.

Page 26

Panel 2

See last page, panel 4 notes.

Panel 5

Toulouse-Lautrec did indeed paint posters for Le Moulin Rouge (“The Red Mill”) night club.

“I say, you fellows!” : a favourite exclamation of Billy Bunter. And, if you don’t know who he is, see the Wikipedia page.

“A restorative”; a common term for an alcoholic drink in the world of PG Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster, a big influence on the character of Roderick.

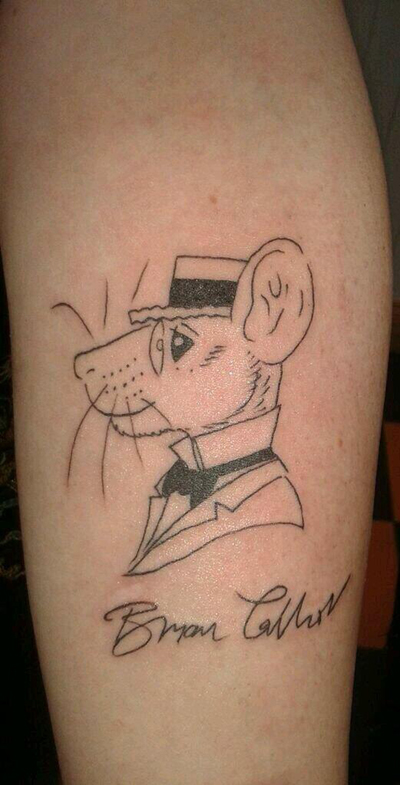

Speaking of Roderick, at a comic convention around the time Bête Noire was published, a fan showed me his tattoo of a sketch of the character that I’d done at a previous convention for him. Here it is.

The pig by the laughing cow to the right proclaims “Piggin’ grand”, a reference to the conversational style of Uncle Pig, the fictional editor of British children’s comic Oink (1986 – 1988). I deliberately put the two characters together for the French edition, when I was going to suggest that their version have tail of the balloon going to the cow instead, who could be saying “Vachement gènial!” (“Really bloody great!”) “Vachment” (literary “Cowy”). I thought this was really clever till the publishers, Bragelonne, decided to pull the plug on their reprints, despite their edition of Mon Amour winning the Prix SNCF for best bande dessinée 2012, voted for by the nation’s rail passengers.

Page 28

The Giraud Art College frontage is loosely based on the Harris Institute in Preston, Lancashire. We used to live in Bairstow Street, next to it.

Page 29

Panel 1

To the left, a seal is listening to a steampunk Walkman.

Panel 3

The advertising posters seen throughout the Grandville series are all authentic vintage French posters that I’ve adapted by changing the human heads to those of animals.

Panel 4

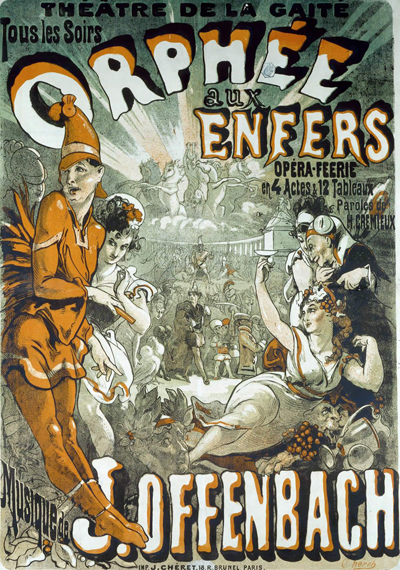

One of the posters seen here, and on the next page and page 33 is advertising Orpheus in the Underworld (Orphée aux Enfer) by Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880). The opera contains Galop Infernal (“The Infernal Gallop”, better known now as the tune to the can-can dance). A character from Greek mythology, Orpheus becomes a clue in the story on page 55 that leads to LeBrock finding Krapaud’s lair.

Also in the background, we can see two members of the religious sect The Silver Path, which is mentioned by Rocher on page 38 and later features in Grandville Noël.

Page 30

Panel 1

This panel is a reworking of Work, the famous Pre-Raphaelite painting by Ford Maddox Brown (1873-1939), which hangs in the City Art Gallery, Manchester, where I’ve visited it many times. He also later did a smaller version, which now hangs in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

Panel 3

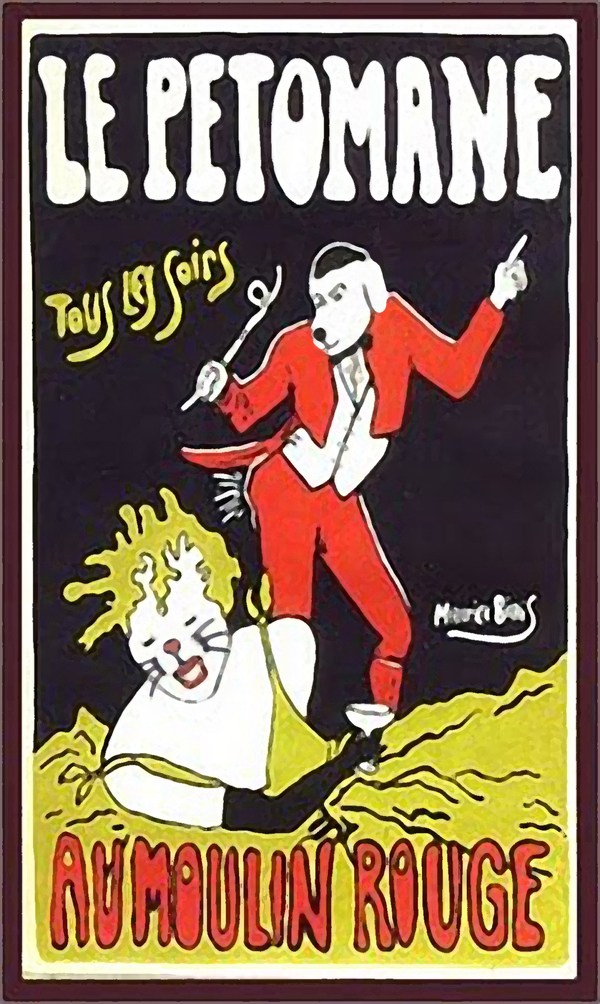

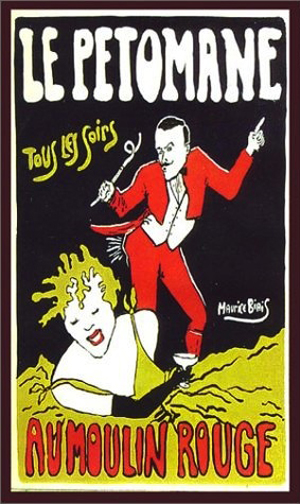

The poster is based on one of the real Le Petomane, Josef Pujol (1857-1945).

A French music hall performer, his act demonstrated his unparalleled ability to fart. He could fart imitations of birds and animals, play tunes and blow out candles at a distance of six feet. In fact, LeBrock’s gibe to Belier to “fart the French national anthem” (Grandville Mon Amour, page 17) is referencing one of his turns. A huge star in his day, he drew audiences larger than the divine Sarah Bernhardt and even played before royalty.

His character can be seen in the background in Madame Tussaud’s waxworks in panel 7, page 26 of Grandville Force Majeure.

Page 31

This walk along the Seine to the Pont Neuf does exist. As I was drawing it, I couldn’t stop Promenade Sentimental from the soundtrack of Diva (1981) running through my head, so it’s become, for me, the incidental music for this scene.

Page 32

Panel 1

I’ll just say two words: frogs legs!

Page 33

Panel 4

“As sure as ferrets are ferrets”: a quote from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. I did try to get as many sayings involving animals into the books as I could without them becoming a noticeable distraction.

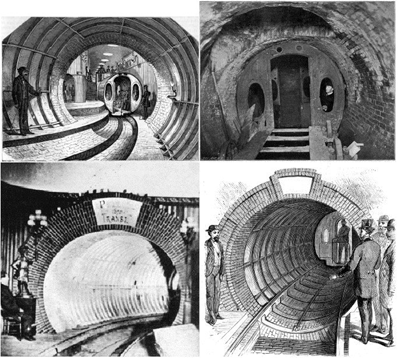

Pneumatic tubeway systems were experimented with in the late 19th Century.

Page 34

Panel 1

This really is what the Prefecture, the headquarters of the Paris Police, looks like. It’s on the Ile de la Cité, near Notre Dame cathedral, on the banks of the Seine.

Page 35

Panel 8

“I could eat a buttered plank”: I don’t know whether this phrase is still in common usage in Wigan, Lancashire, but it certainly was while I was growing up there.

Page 36

The butler, Nistair, in this scene is a homage to Hergé. Nestor was the butler of Captain Haddock’s Marlinspike Hall in the Tintin stories.

I don’t think that I need explain the old upper and upper middle-class custom of “dressing for dinner”? The working-class badger makes several faux pas during this dinner scene, including dipping his bread in his gazpacho and leaning his elbows on the table.

Panel 6

I just noticed that Rocher’s balloon is missing a tail! This will be fixed for any future editions.

Page 37

Panel 2

“Chin-chin”: what the French toast tchin-tchin sounds like.

Panel 5

“They have smaller brains than us”: a common racist fantasy.

Page 38

Panel 1

To put the small plates into the big ones: Mettre les petites plates dans les grands: a French phrase meaning to put on a good spread, to host with great ceremony.

Panel 5

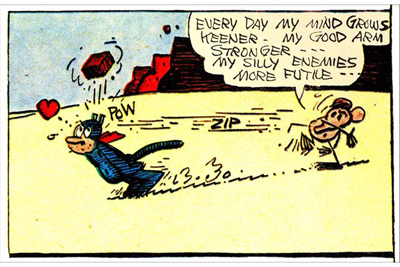

A reference to George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. The common theme of the hugely popular newspaper strips, which were syndicated from 1913 to 1944, was the strange triangle of Krazy, Offica Pup and the mouse, Ignatz. The ambiguously-gendered Krazy loved Ignatz, who hated her/him and ended many of the strips by throwing a brick at her/his head.

The policeman, Offica Pup, was in (unrequited) love with Krazy and devotes his life to stopping Ignatz, but always fails. The strip was noted for its surreal dialogue and shape-shifting backgrounds, and was widely praised by intellectuals as “serious art”. A surrealist piece of work that was around for eleven years the Surrealist manifesto.

Panel 6

“This soup is as cold as a penguin’s arse!”: The conversation is this dinner scene had to be carefully choreographed to cover all the plot points that needed planting within it, not just for this book, but also for the next two, so that’s what I was concentrating on while writing the script. I made a list of everything that needed to be discussed.

Meanwhile, as I typed it, the characters took on a life of their own and started dictating their own lines. When LeBrock came out with this line, it was totally unexpected and I actually burst out laughing. Then Cherie spontaneously started flirting with LeBrock, something else that I’d never planned, but it gave the scene another dimension, so I kept it in.

Page 39

Panel 6

“The Napoleon of Crime”: how Sherlock Holmes refers to his arch-enemy Professor Moriarty. I say “arch enemy” because Moriarty is often referred to as such, and the majority of writers who continue writing Holmes stories or pastiches (and there have been hundreds) usually can’t stop themselves from making him the villain of the piece.

In actuality, out of the sixty original Holmes stories (Four novels and 56 short stories) written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Moriarty only ever appears in one short story, The Adventure of the Final Problem (1893), in which he’s killed at the end, falling over the Reichenbach Falls while fighting with Holmes (who was also presumed dead until Conan Doyle resurrected him in The Empty House (1903)), though he is mentioned in a handful of later stories.

Page 40

Panel 5

The painting on the wall is adapted from Tulip Fields by Claude Monet (1840 – 1926).

Also the the Grandville Bête Noire annotations for pages 41 to 60.